Realistic Economic Modeling Would Require Massive Information Collection, Taking Away Freedom

James Anthony

May 13, 2022

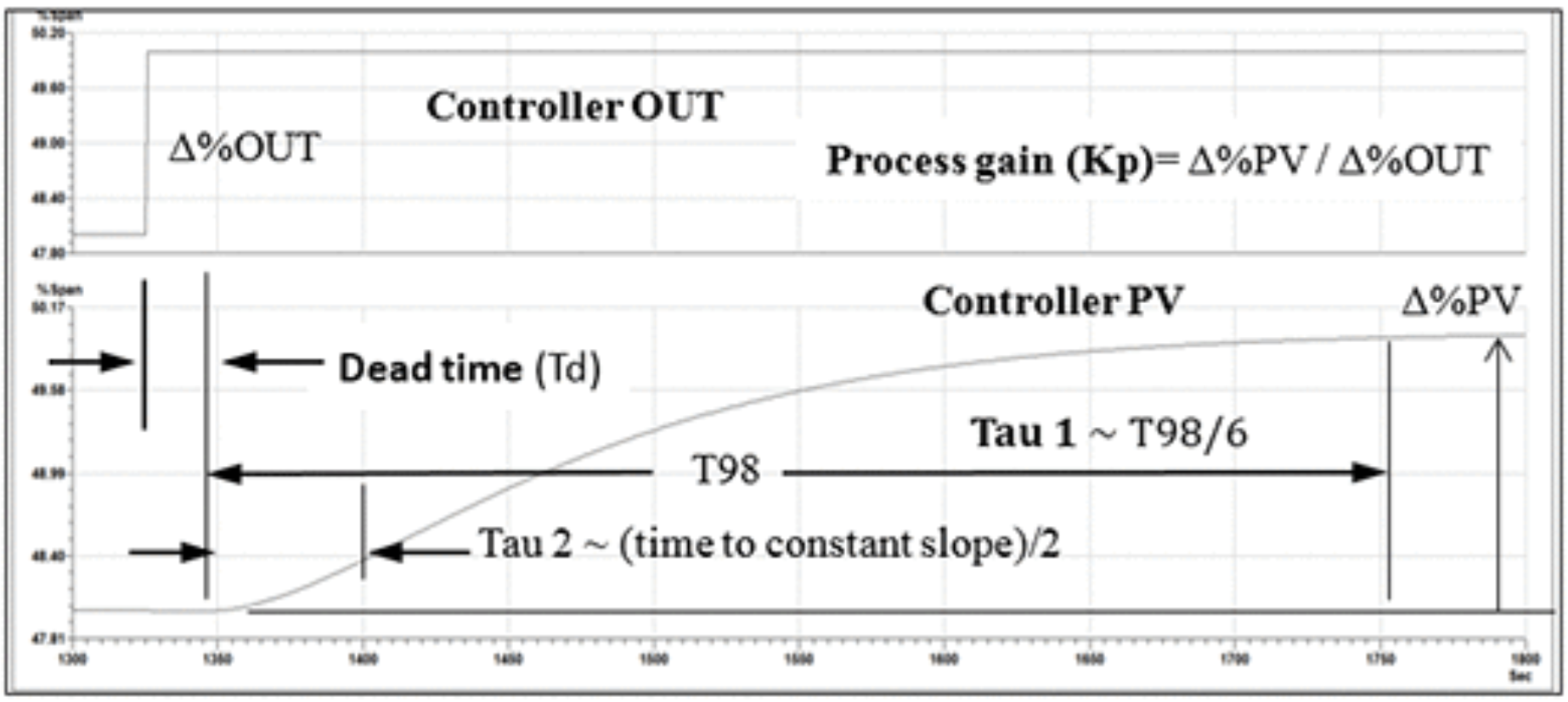

Figure. The step response of a process element’s empirical model that has dead time, primary and secondary lags, and process gain. (James Beall, ISA [1])

Conditions always change. Also, it’s costly to measure information and to use information. These facts greatly hinder economic modeling.

The solution that’s optimal is to not model the economy and to instead just limit governments.

Below, I provide a detailed picture of the feasibility of economic modeling by discussing the real world’s complexity, future advanced modeling, the two basic model types that are currently available, and some striking limitations of current modeling. In the big picture, realistic economic modeling is not needed to guide human action, and would needlessly destroy value and freedom.

People Buy Products, Develop Products, Coerce Others

Every person uses scarce information to forecast what actions are likely to work out best for him.

A person controlling a single process variable by manipulating a single final-control element can be modeled well. A ship helmsman’s direction-control actions were observed to be proportional to the process variable’s error, adjusted if any offset was building up, and adjusted if the error was changing rapidly. Such actions were modeled as proportional-integral-derivative control [2]. A century later, this remains the workhorse algorithm that’s used to control most process variables [3].

A person manipulating many controls to achieve a single objective, though, hasn’t been modeled well.

Individuals’ actions in various economic roles are complex and are affected by many variables:

- When a person buys a product [4], he starts with a lifetime of experience using products and buying products. When a new product is available, he learns about it, possibly from advertising, various reviews, and word of mouth, and always from its sales page or packaging. In considering whether to buy the product, a person factors in his household balance sheet, any expected changes in income or in purchases, and his plans for saving or borrowing. Government people interfere with this buying decision by determining if the product can be sold, changing the product’s form, and increasing the total purchase cost.

- When a person develops a product [5], he starts with a lifetime of using products and buying products and of learning in schools and learning everywhere else. He infers what might appeal to customers. He considers what existing components he could incorporate as-is or improve on. He invests his own time and money, he borrows, he sells to investors, he manages developers, he manages designers, he chooses an asking price, he builds manufacturing capacity, he plans manufacturing, he manages manufacturing, he manages marketers, he managers sellers, and he manages support providers. At many stages and in many tasks he also satisfies government people, including in organizing, financing, obtaining permits, addressing regulations, and paying taxes.

- When a person in government coerces others [6], he considers what’s in it for him to tax or regulate or otherwise favor or disfavor a given buyer or producer. He considers what he can get other people to join with him in imposing.

All these individual actions, on each transaction, determine which products people produce and buy, and in what quantities.

Future Modeling

A person maximizes his satisfaction by making use of his brain’s neural networks.

These neural networks filter the person’s perceptions and distribute control instructions to where they’re needed in the person’s body. The filtering is accomplished by predicting what the person will sense, and the control instruction is accomplished by predicting what precise actions will result from specific instructions. In both cases, the neural networks monitor for how well their predictions are matched by reality, and the neural networks make adjustments as needed, which may include updating their models. In short, the brain’s neural networks continuously model and validate [7].

These neural networks not only are sophisticated mechanisms but also require extensive training using incoming information and trial-and-error action. Since this processing works in humans, this or other processing plausibly could work in artificial intelligence models.

Models of customers choosing among products, even if motivated only to improve targeting in marketing and sales, can easily be anticipated to develop ever-increasing accuracy.

Models of product developers’ creativity and management skills would be complex, but conceivably could be developed along the same path.

Models of government coercers’ creativity and social interactions would be complex and could be developed similarly.

Neural networks trained to spend household budgets, to develop products, or to expand government controls would be highly anthropomorphic both in their actions and in their needs for huge amounts of information inputs and learning—for very-big data.

To date, in contrast, practical models of human behavior have only captured human behavior that’s much simpler, like the helmsman’s control mentioned earlier.

Current Dynamic Process Modeling

Economic change is a dynamic process, which calls for dynamic models.

Dynamic process models are built up of numerous element models. Each element model is of one of two types—an empirical model or a physical model.

Empirical model [8]:

- Idealizes the element as having some of the few dynamic features that are the most common (non-integrating or integrating [9], dead time, lags, gain from input to output). Usually these dynamic features correspond directly to the element’s actual mechanisms. But even if they don’t, they normally will still provide very-useful information to act upon.

- Typically, a change in a single input is modeled as causing a single output to change following a certain pattern over time. The modeler measures this change and correlates it. Very often such a model is surprisingly accurate. If conditions change, normally the model becomes less accurate but still remains very useful as-is. A modeler has the option of measuring the dynamics in different conditions and correlating these effects too.

- Few parameters are needed, and usually these can be estimated helpfully well. The parameters could be optimized by evolutionary learning from dynamic data.

Physical model [10] (of the physics; also called a first-principles model):

- Idealizes the element’s actual mechanisms that most determine the element’s dynamics.

- Inherently suited to respond appropriately when various inputs change in ways that were not previously measured and correlated.

- More parameters normally are needed. For more accuracy, even-more parameters are needed. For complex models, parameters might need to be estimated by learning from dynamic data.

With both types of element models, the commonly-used models don’t capture control valves’ real-world stick-slip behavior, called stiction [11]. A single control valve with stiction can cause plantwide oscillations in many other process variables [12].

Stickiness can be routinely neglected in models of process plants, since oscillations will be seen and mitigated, or preventive control-valve positioners can be installed [13].

Economic Modeling

Stickiness in economics is normal human behavior, is hard to reduce, and is highly destructive. For example, stickiness changed just another avoidable contraction [14] into the sustained Great Depression [15].

Stickiness is characteristic of how producers choose asking prices [16], how government-supervised producers choose the wages to offer [15], and in general how governments take action [17].

The first step in dealing with stickiness is to admit we have a problem.

Regardless of which element types a modeler uses for various elements, the modeler must validate that the resulting model approaches reality closely enough to be useful. For models that are large in scale or that include complex elements or dependencies, validation would demand copious information [18].

For individual buyers, producers, and coercers, the underlying lifetimes of preparation, the balance sheets, and other factors are not measured, reported, and learned.

A modeler could restrict consideration to, say, the aggregated buyers in a nation and the aggregated producers in each sector. At such levels of aggregation, much information is reported.

A modeler conceivably might correlate the rates of product innovation in different sectors by starting from the general observation that the most innovation that makes its way into practical products for sale is the innovation that’s done in the sectors that are the least regulated [19]. The modeler might quantify the many forms that regulation takes and their many impacts, and correlate these negative inputs to the changes in various sectors’ relative outputs. But such modeling hasn’t been done.

The result is that despite its large scale, current economic modeling takes the product mix as frozen into place across all time [20]. There is no modeling of the innovation, the increasing specialization, and the full frictional drags from governments that most-fundamentally determine how the economic value-added changes over time.

So then at present, at most a modeler might, for instance, try to correlate how aggregate transactions might change by sector if a pandemic would spread, or if a government would increase its debt-financed spending.

Even for such limited questions, what modeling has been done has not been adequate. The most-developed correlations have ignored debt [21] and have ignored most actions of governments.

Of course individuals—whose aggregate behavior, after all, is what is being modeled—obviously do pay particularly-close attention to debt, and to all kinds of actions of governments that affect them.

Why Model in Economics? At What Costs?

One consideration about economic modeling that should be foremost is the modeling’s purpose:

- What guidance would a perfect model give individuals that a priori knowledge doesn’t already give individuals?

The answer, from Austrian economics, is straightforward: none at all. Models aren’t needed to show individuals the fact that what’s best is individual freedom [22].

Individual moral behavior is the greatest contributor to making life, liberty, and property secure [23].

For further augmenting this self-restraint, government actions currently have greatly displaced private actions [24]. Government actions can make life, liberty, and property further secure, if these government actions are properly limited.

All other government actions beyond these narrow boundaries destroy value and limit opportunities.

A second consideration about economic modeling that’s inescapable is the modeling’s cost:

- What freedom would immediately be lost if comprehensive information about how individuals act was measured and learned by anyone?

- What freedom would be placed further at risk because of all this information-gathering and use?

- What would it cost to measure, learn from, and model how individuals act?

- Would these certain losses and potential losses be offset by gains?

Losing freedom to a government or a government crony has almost always ended up being deadly [25].

Even short of that, if any resources would be taken from individuals in order to model their actions, the full amount of these resources could no longer be used by the individuals themselves, as buyers or as producers. Individuals would be coerced into doing less for themselves than they otherwise would be able to do.

Individuals’ resulting definitive losses of property and opportunities would not be offset by any hypothetical gains elsewhere.

The best way to optimize people’s actions is to not make measurements that would make people’s work less productive, and to not make models as a way to try to change people, but to just leave people alone.

Ultimately the best model of the real world is the real world itself.

To focus our energies on living in the real world, making the real world better in the ways that we ourselves each have the powers to do—this is ideal.

References

- Beall, James. “Loop Tuning Basics: Complex Process Responses.” InTech, Sep./Oct. 2016, www.isa.org/intech-home/2016/september-october/features/loop-tuning-basics-complex-process-responses. Accessed 13 May 2022.

- Bennett, Stuart. “A Brief History of Automatic Control.” IEEE Control Systems, vol. 16, no. 3, June 1996, pp. 17-25.

- Desborough, Lane, and Randy Miller. “Increasing Customer Value of Industrial Control Performance Monitoring-Honeywell’s Experience.” Sixth International Conference on Chemical Process Control, AIChE Symposium Series, no. 326, 2002, pp. 160-89.

- Heath, Chip, and Jack B. Soll. “Mental Budgeting and Consumer Decisions.” Journal of Consumer Research, vol. 23, no. 1, June 1996, pp. 40-52.

- Holcombe, Randall G. “Progress and Entrepreneurship.” Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics, vol. 6, no. 3, Fall 2003, pp. 3-26.

- DiLorenzo, Thomas J. “Competition and Political Entrepreneurship: Austrian Insights into Public-Choice Theory.” The Review of Austrian Economics, vol. 2, no. 1, Dec. 1988, pp. 59-71.

- Adams, Rick A., et al. “Predictions Not Commands: Active Inference in the Motor System.” Brain Structure and Function, vol. 218, no. 3, May 2013, pp. 611-43.

- Marlin, Thomas E. Process Control: Designing Processes and Control Systems for Dynamic Performance. 2nd ed., McMaster University, 2015, pp. 175-206.

- Rice, Bob, and Doug Cooper. “Recognizing Integrating (Non-Self Regulating) Process Behavior.” Control Guru, 9 Apr. 2015, controlguru.com/recognizing-integrating-non-self-regulating-process-behavior/. Accessed 13 May 2022.

- Marlin, Thomas E. Process Control: Designing Processes and Control Systems for Dynamic Performance. 2nd ed., McMaster University, 2015, pp. 49-95.

- Srinivasan, Ranganathan, et al. “Issues in Modeling Stiction in Process Control Valves.” 2008 American Control Conference, IEEE, 2008, pp. 2274-9.

- Choudhury, MAA Shoukat, et al. “Root Cause Diagnosis of Plantwide Disturbance Using Harmonic Analysis.” IFAC Proceedings Volumes, vol. 42, no. 11, 2009, pp. 297-302.

- McMillan, Gregory, and Pierce Wu. “Valve Response: Truth or Consequences.” Control Global, 2016, www.controlglobal.com/assets/wp_downloads/pdf/Valve-Response-Truth-or-Consequences-by-Gregory-McMillan-and-Pierce-Wu.pdf. Accessed 13 May 2022.

- Anthony, James. “George Washington’s Error and the Corruption of Banking.” American Thinker, 22 May 2019, www.americanthinker.com/articles/2019/05/george_washingtons_error_and_the_corruption_of_banking.html. Accessed 13 May 2022.

- Ohanian, Lee E. “What – Or Who – Started the Great Depression?” Journal of Economic Theory, vol. 144, no. 6, Nov. 2009, pp. 2310-35.

- Zbaracki, Mark J., et al. “Managerial and Customer Costs of Price Adjustment: Direct Evidence from Industrial Markets.” Review of Economics and Statistics, vol. 86, no. 2, May 2004, pp. 514-33.

- Anthony, James. “Changing Government by Stepping, Phasing, or Doing.” rConstitution.us, 23 Apr. 2021, rconstitution.us/changing-government-by-stepping-phasing-or-doing/. Accessed 13 May 2022.

- Sornette, Didier, et al. “Algorithm for Model Validation: Theory and Applications.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 104, no. 16, 17 Apr. 2007, pp. 6562-67.

- Winston, Clifford. “US Industry Adjustment to Economic Deregulation.” Journal of Economic Perspectives, vol. 12, no. 3, Summer 1998, pp. 89-110.

- Axtel, Rob, and J. Doyne Farmer. “Old Economic Models Couldn’t Predict the Recession. Time for New Ones.” Medium, 5 Apr. 2018, sfiscience.medium.com/old-economic-models-couldnt-predict-the-recession-time-for-new-ones-3bcf990d5aa1. Accessed 13 May 2022.

- Keen, Steve. “Modeling Financial Instability.” Steve Keen’s Debtwatch, 2 Feb. 2014, www.debtdeflation.com/blogs/2014/02/02/modeling-financial-instability/. Accessed 13 May 2022.

- Rothbard, Murray N. “Mises and the Role of the Economist in Public Policy.” The Meaning of Ludwig von Mises: Contributions in Economics Sociology, Epistemology, and Political Philosophy, edited by Jeffrey M. Herbener, Mises Institute/Kluwer, 1993, pp. 193-208.

- Anthony, James. “Economic Growth Is a Natural Effect of Christianity.” rConstitution.us, 3 Dec. 2021, rconstitution.us/economic-growth-is-a-natural-effect-of-christianity/. Accessed 13 May 2022.

- Stringham, Edward Peter. “Market Chosen Law.” Journal of Libertarian Studies, vol. 14, no. 1, Winter 1998-9, pp. 53-77.

- Anthony, James. “Socialism Kills Freedom.” rConstitution.us, 26 Mar. 2021, rconstitution.us/socialism-kills-freedom/. Accessed 13 May 2022.

James Anthony is the author of The Constitution Needs a Good Party and rConstitution Papers, publishes rConstitution.us, and has written in The Federalist, American Thinker, Foundation for Economic Education, American Greatness, and Mises Institute. Mr. Anthony is an experienced chemical engineer with a master’s in mechanical engineering.

Commenting

- Be respectful.

- Say what you mean.

Provide data. Don’t say something’s wrong without providing data. Do explain what’s right and provide data. It’s been said that often differences in opinion between smart people are differences in data, and the guy with the best data wins. link But when a writer provides data, the writer and the readers all win. Don’t leave readers guessing unless they go to links or references. - Credit sources.

Provide links or references to credit data sources and to offer leads.