Election Power and Duty Are Delegated to Legislators and Electors

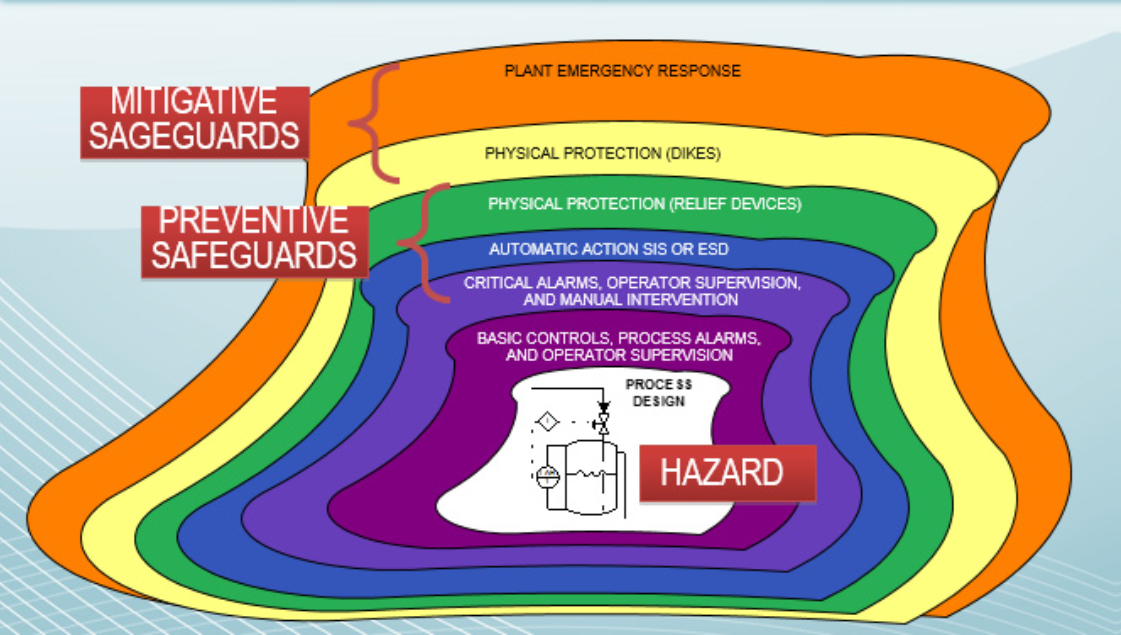

Voters are protected from consequential losses only if at least one independent protection layer works.

James Anthony

November 27, 2020

Figure: Ronald J. Willey [1]

In Layer of Protection Analysis, a process is protected from consequential losses if at least one independent protection layer works [1].

In our elections, Progressive Democrats have worked to strip away preventive safeguards. Republican Progressives have colluded by not asserting their constitutional powers that would have maintained prior preventive safeguards and that would have let them add stronger preventive safeguards.

Now the initial votes for 2020 have been cast. Baked into these initial votes, we now are stuck with harvested ballots, ballots that don’t verify who voted and when, widely-deployed software that has counted small but decisive fractions of Trump votes as Biden votes, vote counting that was halted and delayed, poll observers who were denied access, suspiciously-high supposed turnouts in critical Biden-favoring precincts, impossible leaps up by upwards of 100,000 votes that went for Biden 100%, and more.

For this election, our primary protections have now been reduced to mitigative safeguards: state legislators, and electors.

State Legislators Have Power and Duty to Direct Manner of Appointing Electors

The Constitution says that Congress may determine the time of choosing the presidential electors [2], but each state’s legislature may direct the manner the state appoints the electors [3].

The Constitution initially said that each state’s legislature chose the state’s senators [4].

The Constitution doesn’t say that state executives’ power limits state legislatures’ power to prescribe the manner of appointing electors, and the Constitution is the supreme law [5], so state legislatures have independent power to prescribe the manner of appointing electors.

United States Code title 3, section 2 seconds this by stating that “Whenever any State has held an election for the purpose of choosing electors, and has failed to make a choice on the day prescribed by law, the electors may be appointed on a subsequent day in such a manner as the legislature of such State may direct.” [6]

State legislatures, further, have the duty to direct the manner of appointing electors.

In the Declaration of Independence, the grievances are against the executive’s injuries and usurpations, all of which had the direct object of establishing absolute tyranny [7].

The Constitution is intended to prevent such tyranny, in significant part by structuring the national government so that the legislative powers are stronger than the executive powers, and the executive powers are stronger than the judicial powers. The legislature passes bills, the executive doesn’t pass but just enforces the resulting laws, and judges don’t enforce but just opine on cases which the executive then enforces.

The Constitution extends such preventions of tyranny to every state by guaranteeing to every state a republican form of government [8].

A state legislature that didn’t direct the manner the state appointed the electors would fail to prevent tyranny in its state. Since each state legislator’s duty to support the Constitution [9] includes a duty to provide a republican form of government, this requires that each state legislator uses his constitutional power to direct the manner in which the state appoints presidential electors.

To protect against consequential losses of election integrity, the state legislators must provide independent protection.

Electors Have Power and Duty to Vote Independently

The intended role of presidential electors is clearest from the overall context: the Constitution divides powers so each is offset by others.

Each power of the sovereign people [10] is reserved to the people, delegated to the state governments, or delegated to the national government [11].

The national government’s powers are vested as separate legislative [12], executive [13], and judicial [14] powers.

The national government’s legislative powers are vested in the Senate and the House of Representatives [12]. Bills must be either signed by the president or reconsidered and passed by 2/3 majorities in both houses [15].

Cases under the resulting laws [16], or under analogously-lawful treaties [17] passed by 2/3 majorities in the Senate and made by a president [18], are subject to the judicial power vested in the Supreme Court.

In criminal prosecutions [19] and in suits at common law where the value in controversy exceeds $20 [20], no fact tried by a jury can be reexamined other than according to the rules of the common law [21]. In criminal prosecutions, the accused enjoys the right to have the assistance of defense counsel [22].

Presidential electors meet in their respective states, separate from electors of other states. Each elector must vote for at least one presidential candidate or vice presidential candidates who is not an inhabitant of the elector’s state [23]. So the electors are more independent from presidential candidates, and each state’s electors are fully independent from other states’ electors.

Each government officer, both in the state governments and in the national government, in all branches, is bound by oath or affirmation to support [24] or protect [25] the Constitution.

Throughout all of these definitive provisions, then, power is divided, and each divided power is vested exactly as needed to make it independent of the other powers. This independence is reinforced by each individual officer’s oath or affirmation.

In short, these provisions establish multiple independent layers of protection [1].

Considering that the Constitution provides independent layers of protection that include the people, the state governments as a whole, the state legislatures, the House, the Senate, the president, judges, juries, and defense counsel, it’s clear, given this context, that the Constitution provides presidential electors as another independent layer of protection.

To protect against consequential losses of election integrity, the presidential electors must provide independent protection.

Constitutionally, the State Legislatures and Presidential Electors Must Each Independently Protect the Legitimate Voters

It might be good to audit votes to apply the state legislatures’ direction of the manner of appointing electors [26]. It might be better to hold new elections that enforce tighter directions [27].

But regardless of whether such mitigative safeguards are applied, the final say will come later, in the final actions of the state legislators and the presidential electors.

Each state legislature must assert its independent power to prescribe the manner of appointing presidential electors. This manner must reflect the legislators’ best judgments of what would have been decided by the legal votes that were cast.

Presidential electors must assert their independent power to vote for the presidential candidate and vice-presidential candidate. These votes must reflect the electors’ best judgment of what would have been decided by the legal votes that were cast.

Voters will be protected from consequential losses only if at least one independent protection power is used [28] now.

References

- Willey, Ronald J. “Layer of Protection Analysis.” Procedia Engineering, vol. 84, 2014, pp. 12-22.

- USA Constitution, art. II, sec. 1, cl. 4.

- USA Constitution, art. II, sec. 1, cl. 2.

- USA Constitution, art. I, sec. 3, cl. 1.

- USA Constitution, art. VI, cl. 1.

- United States Code, title 3, sec. 2.

- USA Declaration of Independence, 1776.

- USA Constitution, art. IV, sec. 4.

- USA Constitution, art. IV, sec. 3.

- USA Constitution, preamble.

- USA Constitution, amend. 10.

- USA Constitution, art. I, sec. 1.

- USA Constitution, art. II, sec. 1, cl. 1.

- USA Constitution, art. III, sec. 1.

- USA Constitution, art. I, sec. 7, cl. 2.

- USA Constitution, art. III, sec. 2, cl. 1, judicial clause.

- USA Constitution, art. III, sec. 2, cl. 1, treaties.

- USA Constitution, art. III, sec. 2, cl. 2.

- USA Constitution, amend. 6, jury trial.

- USA Constitution, amend. 7, right to jury in civil cases.

- USA Constitution, amend. 7, reexamination clause.

- USA Constitution, amend. 6, right-to-counsel clause.

- USA Constitution, amend. 12.

- USA Constitution, art. VI, cl. 3.

- USA Constitution, art. II, sec. 1, cl. 8.

- “Post-Election Audits.” NCLS.org, 25 Oct. 2019, www.ncsl.org/research/elections-and-campaigns/post-election-audits635926066.aspx. Accessed 27 Nov. 2020.

- Horowitz, Daniel. “Horowitz: 9 Laws Republicans Must Pass to Stop Voter Fraud.” theBlaze.com, 12 Nov. 2020, www.theblaze.com/op-ed/ready-horowitz-9-laws-republicans-must-pass-to-stop-voter-fraud. Accessed 27 Nov. 2020.

- Anthony, James. rConstitution Papers: Offsetting Powers Secure Our Rights. Neuwoehner Press, 2020.

James

Anthony is the author of The Constitution Needs a Good Party and rConstitution

Papers, publishes rConstitution.us, and has written articles in The Federalist,

American

Thinker, and Foundation

for Economic Education. He is an

experienced chemical engineer with a master’s in mechanical engineering.

Commenting

- Be respectful.

- Say what you mean.

Provide data. Don’t say something’s wrong without providing data. Do explain what’s right and provide data. It’s been said that often differences in opinion between smart people are differences in data, and the guy with the best data wins. link But when a writer provides data, the writer and the readers all win. Don’t leave readers guessing unless they go to links or references. - Credit sources.

Provide links or references to credit data sources and to offer leads.