Neighborhood Cities Increase Freedom

If people in similar neighborhoods secede from big cities to form neighborhood cities, people everywhere will become more free.

James Anthony

December 26, 2020

In 1897, a Progressive who studied city governments concluded that if socialism ever comes, it more than likely will come by way of the city [1].

Now, city officials who enable monopolistic public sector unions, and the members of these unions, both are core members of today’s socialist elite [2]. Big cities’ representatives dominate many state governments, and cities’ representatives dominate the national government. As of 2018, the districts that were predominantly either urban, urban-suburban, or inner-ring suburban elected 64% of House Democrats [3], who now are overtly socialist.

Dividing Problems into Simpler Components

Meanwhile, people, in the course of just going about their normal lives, regularly choose to live in specific neighborhoods. These deliberate, careful choices sort people into relatively-homogenous groups.

In any given neighborhood, the people who choose to live there would like their city government to fit their preferences more closely.

Developing a distinct government that matches the preferences of a distinct neighborhood is the established practice in newer parts of the USA. Suburban regions are almost all divided into smaller entities—cities, boroughs, townships, towns, or villages [4].

Urban regions are the behind-the-times exception. Big-city cores are almost all each controlled by centralized big governments.

Small, neighborhood-based city governments would take people’s careful selections of where to live and would put all this existing self-organizing to further use to fix city problems. Neighborhood cities would carve up big city-government problems into manageable, bite-sized pieces. This decentralization would enable people to experiment, learn what works best, and adopt best practices as soon as each neighborhood city’s people are ready.

Give City Governments an Inch and They’ll Take a Mile

At the time the Constitution was ratified, the people reserved to themselves the powers over religion, education, and social services. State governments had power over militias, local governments, property not in interstate commerce, family affairs, criminals, intrastate civil disputes, and businesses [5]. City governments were delegated most power over criminal law enforcement and some power over businesses.

At first, USA governments at all levels of operation were small, and the city governments were the smallest [6]. The first steady, unreversed growth among USA governments was the growth of city governments [7]. The bigger the city, the bigger was the city-government growth [8]. By 1890, the national government and the state governments had both been outgrown by the city governments [8].

City-government growth continues today. The national government grew much differently, mostly only ratcheting up through world wars. The state governments grew more slowly, taking until 1972 to overtake the city governments again. But except around World War II, when city governments temporarily were crowded out, city governments have mostly just kept growing [9].

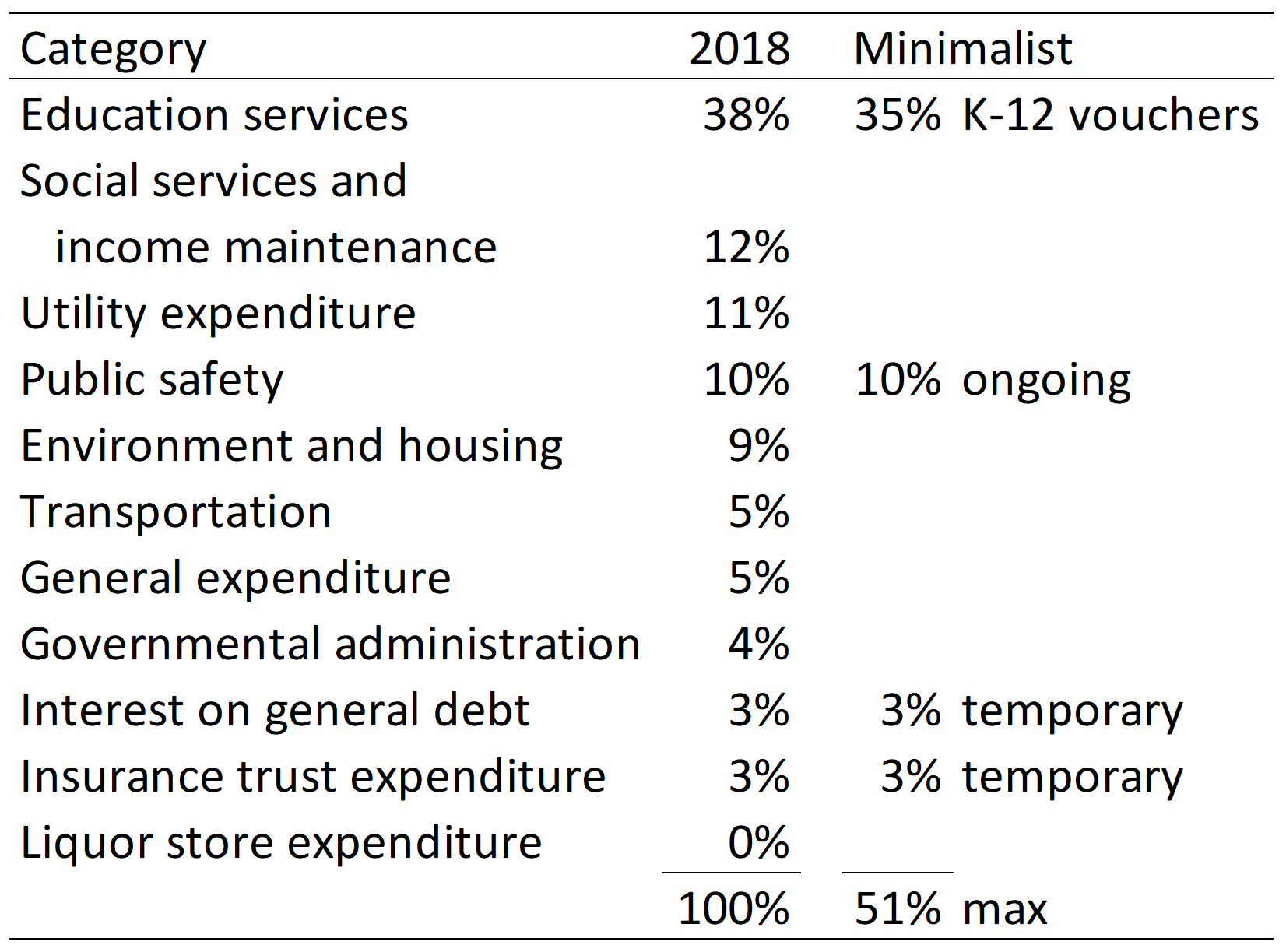

The resulting local-government spending nowadays is summarized in the table.

Table. Local-government spending by category in 2018 [10],

and potential spending in minimalist neighborhood cities

Parents as Customers, and Public Safety First

Minimalist spending would start by only retaining the spending in a few of the current categories. In those categories, minimalist spending could start at current levels and then would fall considerably.

K-12 school spending could be transferred to parents’ control through vouchers that have no strings attached.

Change that’s fast and complete is always best [11], both to solidify better political coalitions and to deliver the most improvement for the longest.

Here, if change is fast, then at first the nearby nongovernment schools would temporarily need to take extra steps to satisfy the extra demand, so at first their marginal costs would be higher than usual.

Transitional costs that are higher than usual for nongovernment schools could be easily covered by spending at the current levels, since compared to government schools, nongovernment schools usually average half the cost [12]. Vouchers could at first just take the current spending for government schools and transfer this whole amount directly to parents.

As long as these high spending levels, the legacy of the government monopoly on schools, would later be cut back, the existing nongovernment schools would soon reoptimize their operations. Also, other nongovernment schools would soon start up. Under these competitive pressures, prices would soon be driven back to the longstanding norm of half the cost of government schools. From there, given the greater competition and innovation, prices would steadily improve further.

On top of that, given vouchers with no strings attached, parents would have maximum freedom to vote with their feet, and this would provide further pressure. Under all the competitive pressures, choices and quality would also steadily improve [13].

Public-safety spending—the table’s only substantial category that the Constitution’s ratifiers agreed was appropriate for local governments—initially could be kept as-is.

Over time, especially as nearby neighborhood cities were organized and made the local market larger, neighborhoods could sooner or later purchase these services from competitive security-business startups, and quality and pricing would improve.

By focusing attention on this core function and on the results, a given neighborhood-city’s people might decide either to buy more public-safety services or to buy fewer, whichever improves these people’s quality of life.

General debt and insurance-trust pension spending would be immediately stopped from growing larger, could be fully funded if needed, and could be retired if desired.

Free People Are Generous and Shop Well

The remaining, non-minimalist spending would be left to individuals to choose for themselves.

Social services, income maintenance, and housing are naturals to be provided by individuals working directly through charities, as was done on a larger scale in the past, improving quality and pricing [14].

Utilities, environmental, transportation, and liquor stores are naturals to be bought by individuals [15] directly from businesspeople, as is done in many areas already, improving quality and pricing.

General expenditures and government administration would be negligibly small once overall operations were minimalist.

Small Steps Bring Big Freedom

Most of the skill and effort required to make neighborhood cities work well are already amply provided by people anyway in the natural way—by individually self-organizing—when people choose to live in a given neighborhood. To use these careful choices to best advantage only requires two smaller steps further:

- Assert the right to self-determination [16] in local government.

- Support representatives who don’t simply take legacy-city governments’ customary practices and reanimate these on a smaller scale, but who instead make the new neighborhood-city governments better by making them minimalist.

Relatively-small steps in the right direction can make freedom grow substantially.

References

- Wilcox, Delos Franklin. The Study of City Government; An Outline of the Problems of Municipal Functions, Control and Organization. New York, Macmillan, 1897, p. 235.

- Ring, Edward. “How America’s Cities Became Bastions of Progressive Politics.” American Greatness, 14 Nov. 2020, amgreatness.com/2020/11/14/how-americas-cities-became-bastions-of-progressive-politics/. Accessed 26 Dec. 2020.

- Florida, Richard, and David Montgomery. “How the Suburbs Will Swing the Midterm Election.” Bloomberg CityLab, 5 Oct. 2018, www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-10-05/the-suburbs-are-the-midterm-election-battleground. Accessed 26 Dec. 2020.

- Decentralization and Local Democracy in the World: First Global Report by United Cities and Local Governments, 2008. The World Bank, 2009, p. 239.

- Natelson, Robert G. “The Enumerated Powers of States.” Nevada Law Journal, vol. 3, no. 3, Spring 2003, pp. 469-94.

- Holcombe, Randall G., and Donald J. Lacombe. “The Growth of Local Government in the United States from 1820 to 1870.” The Journal of Economic History, vol. 61, no. 1, Mar. 2001, pp. 184-9.

- Wallis, John Joseph. “American Government Finance in the Long Run: 1790 to 1990.” Journal of Economic Perspectives, vol. 14, no. 1, Winter 2000, pp. 61–82.

- Legler, John B., et al. “U.S. City Finances and the Growth of Government, 1850-1902.” The Journal of Economic History, vol. 48, no. 2, June 1988, pp. 347-56.

- Chantrill, Christopher. “US Government Spending History from 1900.” usgovernmentspending.com, www.usgovernmentspending.com/past_spending. Accessed 26 Dec. 2020.

- “2018 State & Local Government Finance Historical Datasets and Tables.” Census.gov, 8 Oct. 2020, www.census.gov/data/datasets/2018/econ/local/public-use-datasets.html. Accessed 26 Dec. 2020.

- Havrylshyn, Oleh, et al. “25 Years of Reforms in Ex‐Communist Countries: Fast and Extensive Reforms Led to Higher Growth and More Political Freedom.” Policy Analysis, 795, 2016.

- van Kipnis, Gregory. “Reform the K-12 Government- School Monopoly: Economics and Facts.” AIER.org, 2 Sep. 2020, www.aier.org/article/reform-the-k-12-government-school-monopoly-economics-and-facts/. Accessed 26 Dec. 2020.

- Rockwell, Llewellyn H., Jr. “What If Public Schools Were Abolished?” Mises.org, 14 July 2020, mises.org/library/what-if-public-schools-were-abolished. Accessed 26 Dec. 2020.

- Edwards, James Rolph. “The Costs of Public Income Redistribution and Private Charity.” Journal of Libertarian Studies, 21, no. 2, 2007, pp. 3–20.

- von Mises, Ludwig. Bureaucracy. Yale University Press, 1941, pp. 20-1.

- von Mises, Ludwig. Liberalism in the Classical Tradition. Translated by Ralph Raico, 3rd ed., The Foundation for Economic Education and Cobden Press, pp. 108-10.

James Anthony is the author of The Constitution Needs a Good Party and rConstitution Papers, publishes rConstitution.us, and has written articles in The Federalist, American Thinker, and Foundation for Economic Education. He’s an experienced chemical engineer with a master’s in mechanical engineering.

Commenting

- Be respectful.

- Say what you mean.

Provide data. Don’t say something’s wrong without providing data. Do explain what’s right and provide data. It’s been said that often differences in opinion between smart people are differences in data, and the guy with the best data wins. link But when a writer provides data, the writer and the readers all win. Don’t leave readers guessing unless they go to links or references. - Credit sources.

Provide links or references to credit data sources and to offer leads.